Mastodon & moderation

I’m on the board of a regional burn, Burning Flipside. We have to deal with banning people and it’s the hardest, most time-consuming thing we do. There are some analogies to Mastodon bans and defederations that might be useful.

One illuminating difference is that our ban list is private: we treat it as very secret. But there are frequent suggestions that we should share our ban list with other regionals and accept ban lists from other regionals. And in fact, there’s at least one regional that proactively shares its banning decisions.

There’s a certain logic to this, because the populations of regional burns overlap a lot. People from one regional often go to others, including bad actors, and sometimes when a bad actor gets “run out of town,” he (it’s usually a he) moves on to another. So I understand why people would want shared ban lists.

But being notified of another org’s banning decision puts us in an awkward place: it creates pressure on us to respond to it somehow. But our own policies require firsthand reports, which one of these outside-org reports would not be, unless a member of that board is a firsthand reporter. And we might come to a different conclusion than the other org, which could be difficult to explain.

Why do we keep our ban decisions secret? Partly it’s out of liability concerns. We don’t want to be accused of libeling/slandering someone. Also, our decisions don’t always make sense out of context: we once had to “ban” a toddler who was at the center of a custody fight between two parents. Sometimes knowing who has been banned would convey information about who made the report to us in the first place, which we would want to avoid at all costs. Every decision is made in a unique context, and it would be impossible to apply standardized actions consistently.

There’s a difference in the kinds of problems Flipside needs to deal with vs a social-media content moderator. The interactions being reported often happen in private, and even if not, they don’t generally leave an objective record on the Internet. This is tough for me to think through. Speech acts are acts, and the Internet is part of real life. But still, there’s a big difference between being threatened online and being threatened in person, never mind being physically assaulted. The Flipside organization does have a policy not to tolerate “any form of expression that serves to demean, intimidate, or ostracize,” and we have seen some problematic forms of expression in the past, but we haven’t received reports about them since that policy has been in effect. The problems we’re dealing with are more immediate. In any case, I’m not sure how the differences in problems should inform differences in the ways they’re handled. It deserves some thought.

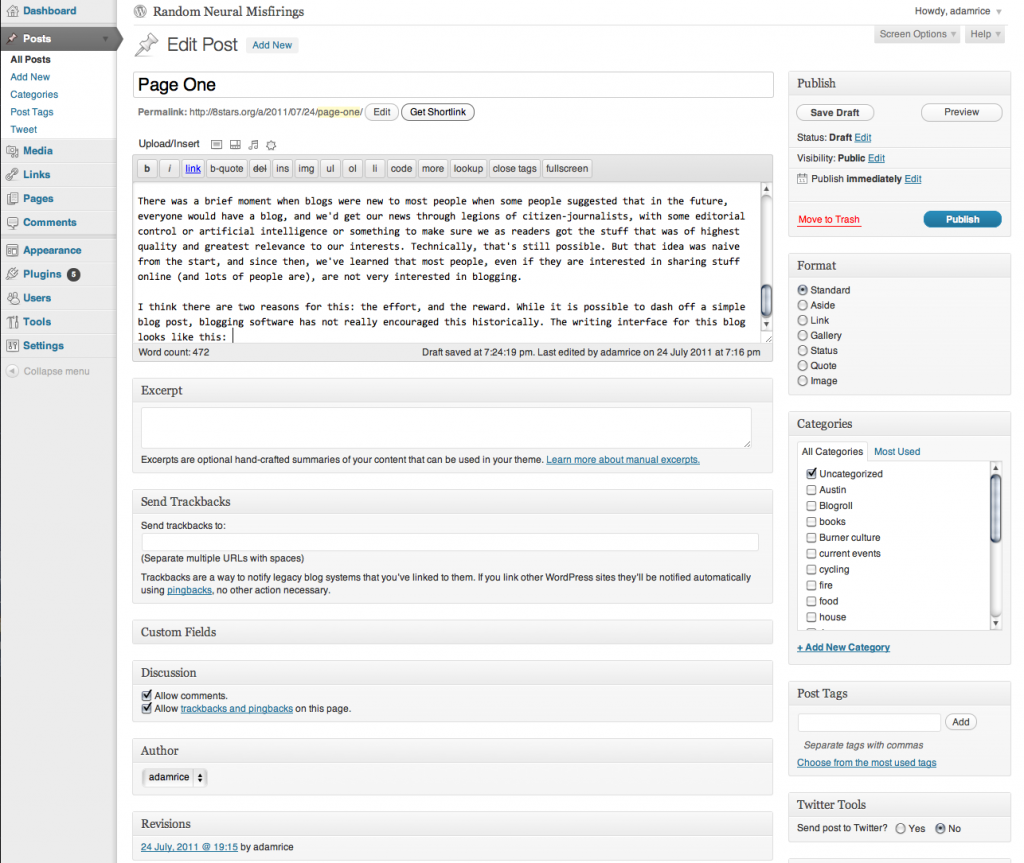

On Flipside’s board, we like to say “we don’t have a lot of options for dealing with problematic participants, and most of them look like hammers.” The Mastodon software offers a number of moderation features, some of which are more subtle than a hammer. As far as I can tell, Mastodon instances don’t publish lists of users under moderation, but in some cases, those users themselves will use another forum to announce that they’re under some kind of moderation.

Then there’s defederation, a way of one instance’s mods saying to another’s “if you won’t moderate your users, we will.” Best as I can tell, defederation is public. Perhaps necessarily so. The instance my first account is on shows which servers it has filtered/silenced/suspended—which is equivalent to applying that moderation to everyone on that instance, remotely.

Right now, it seems like a lot of defederation—or at least chatter about defederation—is happening either because an instance’s moderators have been too hasty or too relaxed about applying moderation. If an instance really has devolved into a hive of scum and villainy, then that’s fair. It’s the healthy thing for the fediverse to do. If it’s a few bad actors on a large instance, it strikes me as procrustean.

This is another way in which the difference between regional burns and Mastodon instances is illuminating. It would be impossible and undesirable for one regional burn to ban everyone from another regional burn.

I’ve got some ideas.

- Fediverse mods need to have a running group chat, so that mods for Instance A can say to the mods at Instance B “I’ve noticed a pattern of problematic posts staying up/unproblematic posts being removed,” and they can talk it out before anyone needs to make a defederation decision. Maybe this already exists.

- It seems likely that Mastodon admins are going to subscribe to external services that make moderation decisions for them. Keeping the lights on is hard enough, dealing with moderation decisions as well is a whole ‘nother ballgame. If this happens, then knowing what moderation service a Mastodon instance subscribes to will tell you something about what kind of place it is.

- Sharing ban lists of individuals between instances, as an alternative to external moderation services, might remove some pressure to defederate, although this might be opening up a bigger can of worms.

Identity is going to be an important aspect of this, because it is possible to change instances, or use multiple instances at the same time. Mastodon provides an easy method to verify your identity, although it requires a bit of nerdiness. This can solve the problem of a public figure who wants to be identifiable but is an asshole. It doesn’t solve the problem of a committed troll, who can easily spool up multiple identities with multiple verifications.

Note: I’ve referred to Mastodon throughout this, but the same idea applies to any service in the fediverse.